As an aspiring marine biologist, Jessica Pollard was nearly finished with her bachelor’s degree and was planning to study altruism in dolphins off the Australian coast when she had an epiphany: she wasn’t excited about potentially long, lonely periods of studying wildlife behavior in the field. But she loved the human connections she made while volunteering at a local health clinic. Soon she was working as a medical assistant at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, which put her on the path to medical school and then building a career as a pediatric hematologist/oncologist.

Now Pollard is a physician and researcher at the Dana-Farber/Boston Children’s Cancer and Blood Disorders Center. With support from Children’s Cancer Research Fund (CCRF), she’s working to find new targeted treatments for high-risk myeloid malignancies.

“I’ve always been someone who likes to solve things,” she said. “I like puzzles. I like sort of the mystery of the diagnosis and then trying to find the best way to solve it. And similarly, I think that’s why I’m attracted to diseases that are higher risk. It took me a while to realize that that’s what I really love about medicine, as well as the relationships.”

A new frontier for clinical MDS research

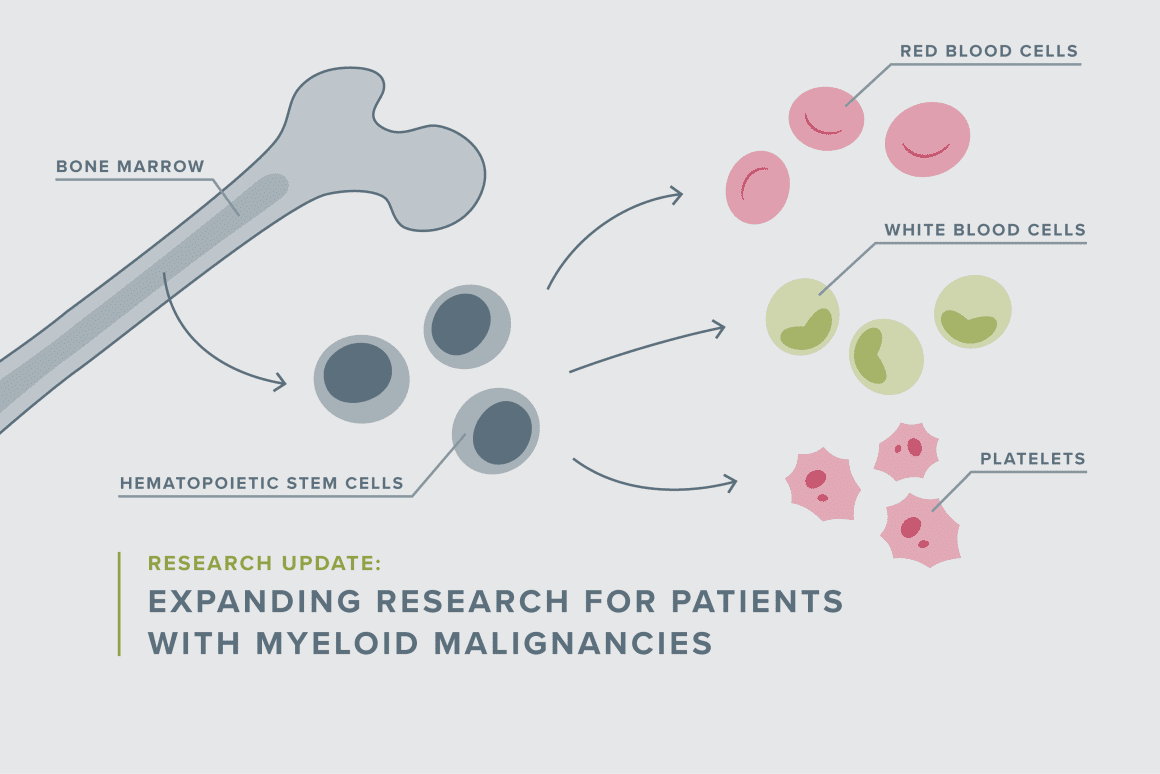

One of the puzzles that Pollard is determined to solve: myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), a bone marrow disorder that affects the development of healthy blood cells. It can occur because of a genetic disposition or develop after chemotherapy. “MDS is a condition that’s very rare in kids, and it’s associated with poor prognosis,” Pollard said. “We don’t know how best to treat it, and treating it just like AML [acute myeloid leukemia] is probably not the right approach.”

Depending on what’s driving a patient’s disease, survival rates for MDS can range from 10 to approximately 50%. Unfortunately, it’s been difficult to learn more because children with MDS are often excluded from clinical trials. That’s because the biology of their disease is different, and they can be challenging to treat and more prone to toxicities, which could complicate the study results for an otherwise promising drug.

“So I wanted to think about a trial that we could really write for them and think about a novel approach that might not be as toxic as a conventional chemotherapy we use for AML,” Pollard explained. “Similarly, I have an interest in bridging the world between what’s called marrow failure and myeloid malignancies. Marrow failure patients have a genetic basis for marrow dysfunction in the myeloid lineage, and some of them are more apt to develop MDS and AML. Importantly, a subset of those with this genetic basis are at very high risk of toxicity from chemotherapy. And I have partnered with colleagues across both hematology and oncology here at Dana-Farber to really try to optimize treatments for that subgroup of patients.”

Testing new treatment options for kids

Pollard’s project focuses on two existing drugs, Azacitidine and Venetoclax, that have been efficacious in adults with MDS. “We think that there are probably differences in adult and pediatric MDS, but anecdotally, we know that kids have responded to this regimen, so it certainly is worth pursuing to see if we get the same good results,” she said.

Pollard’s clinical trial is following two cohorts: The first is kids with MDS and treatment-related malignancies who doctors think can tolerate a full regimen akin to adult dosing, and then another cohort of patients with genetic predisposition syndromes that put them at risk of MDS but also for significant toxicity from chemotherapy. That group will receive, at least initially, a lower dosing of the drug combination. For both subsets, the goal is to use the medications to stabilize their disease before hematopoietic stem cell transplant or, if that is not a viable option, to use it as a maintenance approach.

“You likely need a transplant in order to be a long-term survivor,” Pollard noted. “But you also have to be healthy to get to transplant, which is why this regimen was appealing because some of these kids with a genetic basis can’t tolerate intense chemo, but we know we need to get their disease burden better controlled.”

Investing in the future of better treatments

The clinical trial could also reveal other insights into how to best treat kids with MDS.

“I think we have the opportunity to learn a lot about this rare group of patients that hasn’t been formally studied that extensively,” Pollard said. She and her collaborators are already planning another study that would use a similar cohort model but different drugs that have also shown promise.

But even small clinical trials are very expensive to run, and Pollard said CCRF’s support has been invaluable. She and her colleagues couldn’t get their studies done without organizations like CCRF that focus on pediatric cancer research — an area that is severely underfunded compared to adult cancer research.

“Philanthropy is hugely important, and probably the greatest advances I’ve made in the field have been a byproduct of philanthropy-funded grants,” she said.

And those advances — and the dedication of fellow pediatric cancer researchers — continue to inspire Pollard.

“It is an incredibly collaborative community,” she said. “We all really want to do what’s right for the kids. We are constantly having conversations with colleagues around the country and around the world about how we can work together to improve outcomes, so that gives me great hope.”

Support Groundbreaking Research

Your support propels bold ideas forward and empowers researchers to discover treatments that are better and safer for kids, and ensure every child can have a long, healthy life after cancer.