And why we believe no cancer is too rare to deserve research funding.

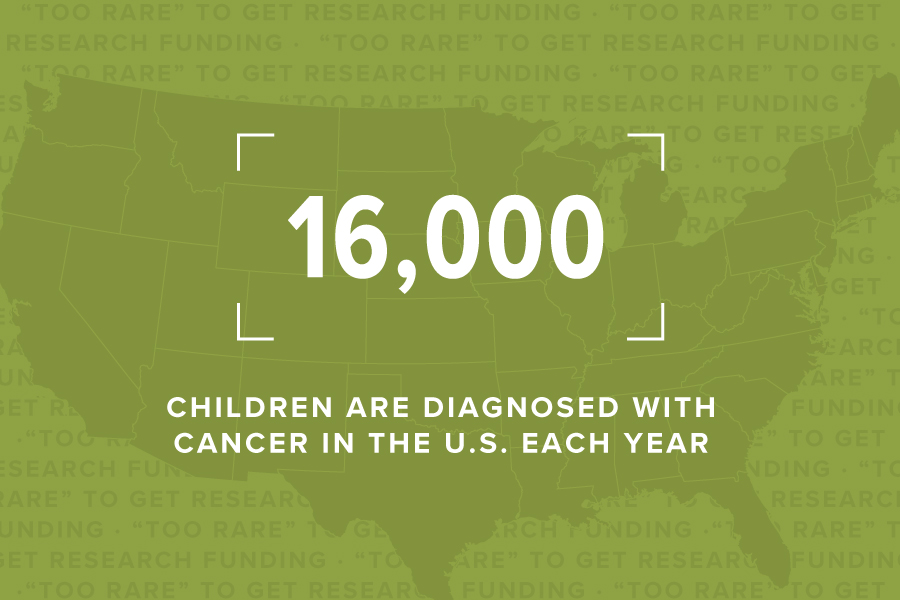

Each day, 43 children are diagnosed with cancer in the United States. That adds up to nearly 16,000 per year. So why is nearly every childhood cancer considered “rare?” And why are so many of those cancers considered too rare to fund research into them by large sources like the National Institute of Health?

Why are childhood cancers often considered “too rare” to research?

In the world of childhood cancers, the word “rare” means very little. The U.S. Rare Diseases Act of 2002 defines a rare disease as one that affects a population smaller than 200,000 – meaning that all childhood cancers are technically considered rare. But just because they’re considered rare doesn’t mean they aren’t complex: for each cancer type, there can be dozens or even hundreds of subtypes, so developing treatments that are widely effective is incredibly difficult. This means that large funding sources like the National Institutes of Health often put their money elsewhere, into research that impacts more people, is further along or easier to execute.

However, cancer is the No. 1 killer of children by disease in the United States. And for some childhood cancers, like hepatoblasoma, incidences of cancer are increasing, as much as 2 to 3% per year.

“Although hepatoblasoma research is very important to the families affected by it, sometimes NIH reviewers just do not see the need to study such a rare cancer,” said researcher, Logan Spector, PhD, chair of the CCRF Research Advisory Committee.

We believe childhood cancer is a growing problem, and it’s a problem worth solving. When researchers and supporters have the resources and determination to solve it, we can make a difference for kids with even the rarest forms of childhood cancer.

Researchers need more data – and support for CCRF helps put that data together.

For a new cancer treatment to become widely available, it has to go through clinical trials, and clinical trials require a certain number of patients to test new treatments for safety and efficacy. This means that clinical trials for childhood cancer require researchers around the country and around the world to collaborate, share data and communicate effectively in order to move research forward. At Children’s Cancer Research Fund, we are encouraging this collaboration by creating grant programs that support it. We award infrastructure grants to help researchers pool, harmonize and leverage existing data that’s currently sitting in silos and separate institutions, or has not yet been analyzed.

For example: with funding from CCRF, Logan Spector, PhD, has collaborated with other researchers around the world to create the world’s largest collection of hepatoblastoma DNA data – so far about 900 in total. Having all this genotype data in one place means Dr. Spector has the best shot at finding what causes this type of cancer.

“We took this project to the NIH seven years ago and they told us this cancer was too rare to care about, and that our sample size wouldn’t work for adult cancers so it couldn’t work in children,” Dr. Spector said. “But we knew this project could make a difference, so we went to CCRF for funding.”

We believe no disease is too rare to deserve research funding.

When researchers don’t have the funding to get the data they need in order to study rare childhood cancers, parents of kids with those cancers are left in the dark, and doctors are left without the information they need to treat their patients effectively.

When Chris’s son Brice was diagnosed with embryonal tumors with multilayered rosettes (ETMR), a rare type of brain tumor, there was almost no body of research to draw from to know how to treat it.

“It’s one thing to get cancer, but when you get one we know nothing about, and one that nobody has ever heard of, you’re really kind of helpless,” Chris said. “You’re really just throwing things against the wall to see what sticks, and that’s a scary thing to do for your child.”

Click here to read Brice's Story - "Win Today."

When Bella was diagnosed with hepatoblastoma at 4 years old, her mom Tabitha’s heart dropped to the floor. No parent ever thinks they’ll hear the words, “your child has cancer.”

“Bella’s cancer is rare, but it’s on the rise in kids, and it’s not being researched enough. When I found that out, all I could think was, ‘Why not?’" Tabitha said. “Why aren’t we there yet? And it’s because researchers don’t have the funding.”

Click here to read Bella's Story - To Change The World.

By supporting Children’s Cancer Research Fund, you’re supporting researchers who believe that with the right resources and collaboration, we can move the needle for even the rarest childhood cancers.

“For a patient’s family, hearing the word ‘rare’ is no consolation at all, because that child is the center of their world,” said researcher Beau Webber, PhD. “[Studying rare cancers] is a huge team effort and it takes a significant amount of funding, but it can be done.”

Your support makes breakthroughs happen.

This is true even when other funding sources are focused somewhere else. Dr. Spector and all of us at CCRF are so grateful for your support. We couldn’t do this without you.