The research questions started to percolate for pediatric oncologist Aman Wadhwa, MD, MSPH, as he made his rounds of the pediatric oncology unit at Children’s of Alabama. “One of the things I really noticed in my first year was there was wide variation in who gets side effects from cancer treatment and how severe,” he said. “I could have patients with the same diagnosis, and one patient will manage treatment relatively well, and another will get really sick to the point of being hospitalized. And I don’t think we really understand why there is a difference.”

But Wadhwa, a researcher at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, is determined to find out. With support from an Emerging Scientist Award from Children’s Cancer Research Fund (CCRF), he is studying the possible connection between body composition and adverse outcomes in children with Hodgkin lymphoma.

Aman Wadhwa, MD, researcher at the University of Alabama at Birmingham

“Anecdotally, patients who have a higher body-mass index tend to have more side effects,” he noted. “The problem with BMI is that it’s a very imperfect measure.”

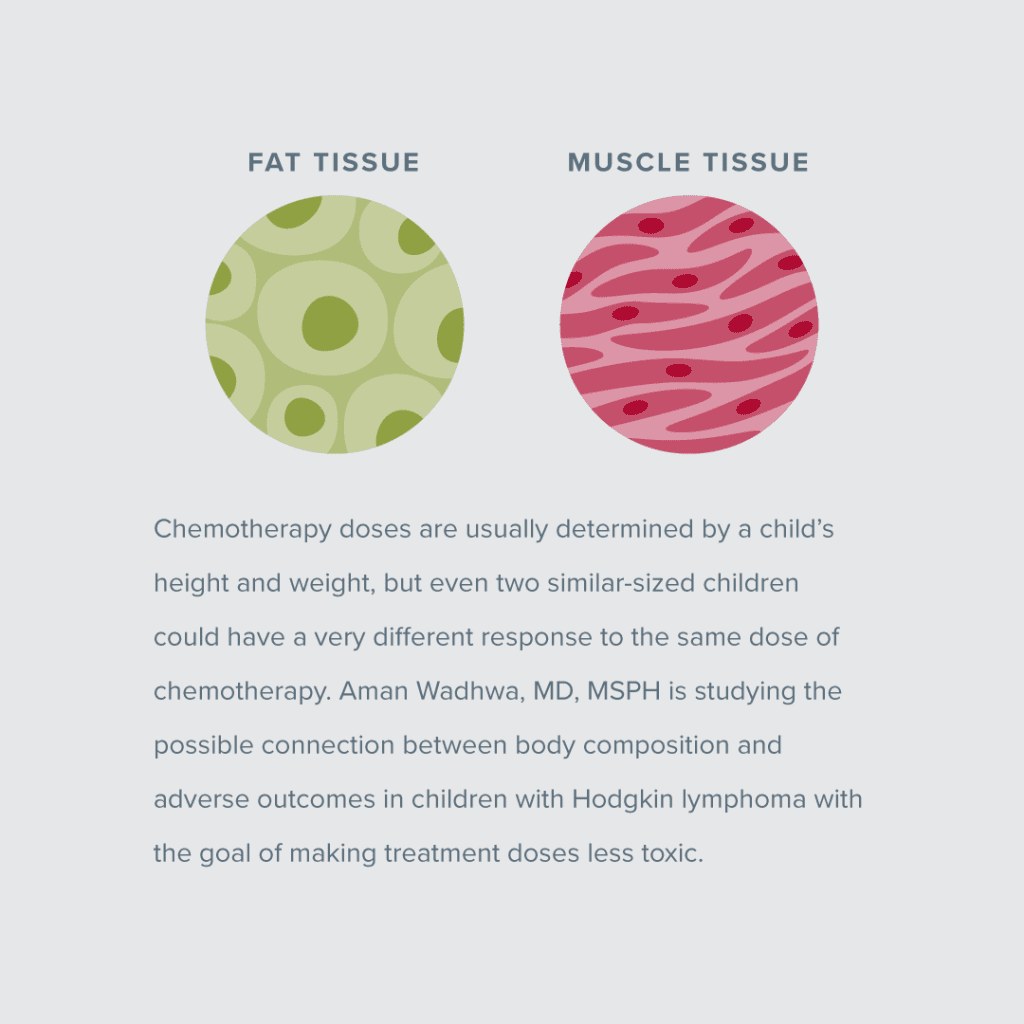

Chemotherapy doses are usually determined by a child’s height and weight, but even two similar-sized children could have a very different response to the same dose of chemotherapy. “What we know now is those patients can look very different inside,” Wadhwa said.

So Wadhwa is using computed tomography (CT) scans to more precisely analyze patients’ muscle and fat tissues to see how that correlates with side effects. An athletic adolescent, for example, could have more muscle mass than a more sedentary peer. Research on adults with cancer has already shown that those with more fat tissues are more likely to suffer from chemotherapy side effects and cancer relapse, but it remains to be seen whether that also holds true for children.

Wadhwa is focusing on Hodgkin lymphoma for practical reasons: patients with that type of cancer regularly have CT scans of the abdomen. His team will use data already collected from hundreds of patients by Children’s Oncology Group.

“We will examine the body composition of children at cancer diagnosis and examine its association with cancer-free survival and serious chemotherapy-related toxicities,” he explained. “We will also examine how body composition changes during cancer treatment and whether that impacts survival.”

At the outset, Hodgkin lymphoma boasts optimistic outcomes: more than 95% of children experience a cure. “Curing patients is not the problem,” Wadhwa said. “The problem is that about 15 to 20% of patients will have a recurrence.” The children whose cancer returns face more intensive treatment regimens — which means their bodies are exposed to more toxicities. And even patients who remain cancer-free can still experience late side effects of chemotherapy as much as 30 years later.

Wadhwa believes that understanding the role of body composition could help, and not just for children with Hodgkin lymphoma.

“Reducing the dose of chemotherapy can affect cure rates, and when kids get really sick from chemotherapy, we often reduce the dose,” he said. “If we can reduce the number of kids who are getting really sick, then we could potentially improve the cure rates.”

If body composition is a significant predictor of adverse cancer outcomes in kids, the next step would be to figure out why and then how to best use that information to help patients.

“I’m most excited about the potential that this research holds,” Wadhwa said. “If we can show that body composition at the time of your cancer diagnosis can be used to either modify your dose of chemo so that’s personalized for you, or if we can set up interventions so you can have fewer side effects, that would lead to better cure rates and quality of life.”

Wadhwa devotes 75% of his time to research, something he couldn’t do without funding from organizations like CCRF.

“The biggest help is giving us the time that the study needs,” he said. “Having this funding certainly allows me to spend the time that I need and also to be able to collaborate with others who are helping to interpret the information. Without this funding and this support, this would be very, very difficult to do.”

Wadhwa is also grateful to continue his frontline work as a clinician — work that motivates him to continue his search for better, less toxic treatments. “It’s such an honor to be trusted with the care of a child who has cancer. Their whole life has just been turned upside down, and those families trust us with the very life of their child,” he noted. “Getting to take care of the patients gives perspective to everything else we do. The more I see patients, the more research questions I get.”

Kids Deserve Better, Safer Treatments

We believe kids fighting cancer deserve treatments that both eradicate their cancer and allow them to live full, healthy lives. Your support is crucial to finding safer, more effective therapies for kids battling cancer.