Troves of data around the globe could get us closer to answering the overarching questions: why do kids get cancer, and how can we treat each child in the best possible way?

But finding and putting this data together cohesively poses one of the biggest challenges in childhood cancer research.

The barrier is so strong, the United States Congress took note and recently passed legislation to overcome it- $50 million per year for the next ten years directed to The National Cancer Institutes for the Childhood Cancer Data Initiative (CCDI).

With the right skills and technology to gather and analyze it, data is the key to overcoming childhood cancers.

In line with the focus on pediatric cancer data, Children’s Cancer Research Fund is proud to support University of Chicago’s Pediatric Cancer Data Commons (PCDC), in addition to Childhood Cancer and Leukemia International Consortium (CLIC) and Children’s Oncology Group (COG)— all which work for better data analysis infrastructure in childhood cancer research.

A lack of data and analysis

Scientists don’t know as much about childhood cancer as adult cancers for a couple reasons: the data is in shorter supply because childhood cancers are rare, and childhood cancers are different from adult cancers. Findings from adult cancer research are not always helpful in learning about kids.

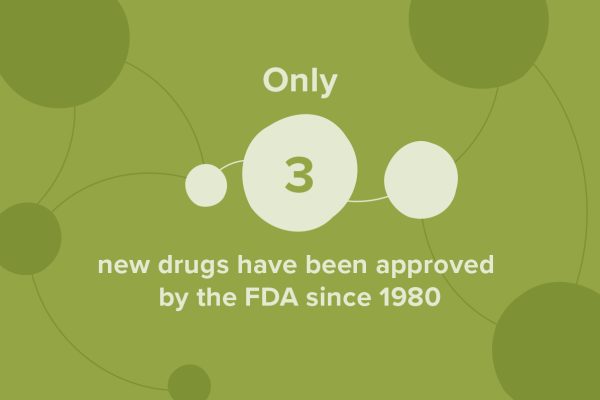

This gap in data has led to a shockingly small number of new drugs approved by the FDA for kids: just 3 since 1980. That is a staggering difference from the 185 approved in the same time frame for adults.

Without the insight data provides, scientists and doctors simply do not have a clear “map” to navigate the diseases effectively nor can they create lifesaving treatments specifically tailored to kids.

Without the insight data provides, scientists and doctors simply do not have a clear “map” to navigate the diseases effectively nor can they create lifesaving treatments specifically tailored to kids.

Logan Spector, PhD epidemiologist and chair of the Childhood Cancer and Leukemia International Consortium (CLIC), notes that data is not as flashy as opening new clinical trials, but it's just as important. It’s actually one of the ways we could fast-track more clinical for kids, because we’ll know more about their diseases.

Broadly, data could help us treat childhood cancer more effectively, in a way specific to each child. It could help us learn more to support diverse populations. It could also show us how cancer and treatment affect survivors and their outcomes in the long term.

More specifically, rich data and analysis could eventually help parents make quality of life decisions for their kids, reduce side effects for a patient and make them less sick, and help doctors avoid what kinds of treatments wouldn’t work, among many other possibilities.

Essentially, data could help prevent undue suffering and save lives.

There are key kinds of data that help scientists:

- Clinical data- includes electronic health records (info on demographics, age, etc.), patient/disease registries (helps inform scientists on how a disease affects populations), imaging (x-rays, MRIs) and clinical trials data (how a treatment was given, how much, and if it worked or didn’t.)

- -omics data- this data focuses on the body’s DNA, proteins, etc. Scientists use this data to learn how these minuscule parts function. The most familiar is “genomic” data, which is information about all the genes in a cell. It is from both the patient and the tumor. “Omics” also includes proteomics, transcriptomics, and many more types of data. It always involves big data.

- Real-world evidence- includes all of the non-clinical data, such as surveys given to patients and families, information about a patient’s environment, data from wearables and sensors, and many other factors, sometimes grouped under the category of “social determinants of health.”

To make data as effective as possible, scientists have to widen their scope internationally to gather enough and fill gaps where it’s scarce. That presents administrative, technological and communication challenges.

Through the PCDC, CLIC, and initiatives with COG, Children’s Cancer Research Fund aims to help researchers:

- Gather the data and fill data holes

- Make the data work together cohesively

- Analyze the data to make it work for kids

Gathering the Data and Filling Data Holes

The barrier:

Gathering the data takes time and expertise

According to Spector, “Simply getting data takes a depressing amount of time.”

Since childhood cancer is considered rare, the data are few and far between. The more data scientists have, the more information they have to see patterns.

“The problem in pediatrics is that the data is spread out with so many people, in small dribs and drabs,” he said.

Scientists have to track down the data in not only different states, but countries.

Countries, and even states, have different guidelines, privacy policies and laws to follow, and parsing that out to get to the data takes skill and expertise. “It’s almost a full time job to keep up with requirements,” he said.

The solution:

Making solid collaborations and partnerships among researchers across states and internationally is key to data-pooling and gathering the most data possible. Collaboration helps establish a common goal and trust with other researchers, and it provides ease of communication for all parties involved. Commons, consortiums, and groups like CLIC, COG, and PCDC foster this.

Hiring researchers who can be trained to know the requirements and systems helps them establish strong collaborations, and they can get to the data faster.

Children’s Cancer Research Fund recently granted funding to help these groups of researchers collaborate and pool epidemiological, clinical, and genomic data nationally, and internationally.

Making the Data Work Together Cohesively

The barrier:

The data doesn’t always work well together.

Data can look like a piece of paper hidden in a file cabinet with a little bit of information written down, other times it looks like a beautifully sophisticated computer program, rich with patient information. The documentation varies depending on the location or institution where it resides.

The difference makes it difficult for scientists to put the data together and see the big picture cohesively.

“We still rely on a lot of manual processes— even some X-rays are still DVDs and CDs,” said Samuel Volchenboum, MD, PhD, Director of Pediatric Cancer Data Commons.

Computers can’t talk to one another because data might be recorded differently, or certain pieces of data might be missing altogether.

The solution:

Researchers like Volchenboum take the data and make it compatible, and in doing so, he can see holes in data and bring everyone up to the same standards.

One way his team does this is by creating data standards using data dictionaries. A data dictionary is a list of agreed upon rules for collection and labeling data, and he’s one of the leaders getting the world to speak the same language about childhood cancers. He’s already been successful with neuroblastoma, a nerve cell cancer.

If scientists around the world apply the rules to their data, the result is a rich and organized universal database with correct, full information that can be accessed everywhere. Once a database is created, its structure can be replicated and edited for a myriad of other diseases, making the process quicker.

Getting the data harmonized helps researchers ensure it’s ready for accurate analysis, the part where they could look at disease patterns, create individualized treatment plans, and a lot more.

Children’s Cancer Research Fund funding will help researchers harmonize epidemiological, genomic, and clinical data through PCDC and CLIC.

Analyzing the Data and Making it Work for Kids

The barrier:

We need better technology and expertise to make data work for kids.

Generally, if a researcher wants to learn something new about childhood cancer, the burden is on them to take the time to find a way to gather the data, wait for approval to access it, find somewhere to store and download all of the information, connect with the right people to analyze it, and come up with a good way to visualize it.

They may have to redo the process over and over to answer different questions, and that takes a lot of time and money. In the meantime, they have to garner the funding to pay for all of these steps.

“We think of data as being free…. but it actually has a physical cost. If you want to handle big data quickly, you need to invest in the computer structure,” Spector says. “The cost of generating data has fallen a lot, but the cost of storing and reading the data has risen. And, infrastructure often entails people, the right people with specialized skills.”

It’s imperative to hire statisticians and bioinformatics experts who can create user-friendly ways for scientists everywhere to access and visualize the data.

The solution:

PCDC, CLIC, and COG, are all finding ways to streamline the data process to alleviate the burden on researchers. Instead of having to redo data work, scientists will be able to build upon what’s already been done with robust visualizations and analytics tools.

They aim to help researchers access the information with ease, so they can focus on asking questions and finding answers to treat rare, deadly diseases. At this point, they could use their time making the data work for them, and ultimately, for kids.

Children’s Cancer Research Fund is providing funding to help these groups hire statisticians and bioinformatics professionals who can find creative, law-compliant ways to analyze data.

In most cases, the childhood cancer data is already out there, waiting to be gathered and turned into answers. In some disease categories, we have a lot more work to do. Our goal at Children’s Cancer Research Fund is to get even the rarest cancer data to a place where resource-sharing is easy and robust.

Then, we can make better treatments for kids and help them thrive.

Your support makes breakthroughs happen.

Childhood cancer research breakthroughs are possible - but it's going to take all of us. With your support, we can fund the incredible scientists working together to create better, safer treatments for childhood cancer.