Surviving childhood cancer is enough of a challenge. Meet an inspiring family who has done it for three generations.

It was 1940, and the parents of four-months-old Dick Ramberg* noticed that his eyes didn’t focus straight ahead. A doctor told his parents the condition was probably a lazy eye and suggested they return in a year for a follow-up appointment. When they did, the diagnosis was shocking. Dick had bilateral retinoblastoma, a cancer of both eyes that occurs in young children.

“The doctor in Minneapolis didn’t know what to do about it,” Dick says of the cancer that, if left untreated, can travel through the optic nerve to the brain. “He told my parents,‘Take him home and enjoy him. He won’t live until he’s two.’”

Now 68-years-old, Dick has greatly surpassed the doctor’s prediction. But the treatments that cured him took their toll. His right eye was removed while Dick was still a toddler. When he was four-years-old, he endured four months of aggressive radiation—a total of 16,000 rads on the left eye alone. That protocol killed the cancer in his left eye but severely damaged the retina. By college, he was functionally blind.

A ripple effect from a rare inheritable cancer

While Dick’s cancer was successfully treated when he was still very young, the disease had a ripple effect that has been felt by two successive generations of his family, including both his children and his only grandchild. That’s because bilateral retinoblastoma is one of the rare forms of childhood cancers that is inheritable.

Even though only five percent of childhood cancers can be passed from one generation to the next, treating them poses unique challenges for doctors. “Children with a familial form of retinoblastoma [retinoblastoma in one eye is not inheritable] may be more at risk of developing other cancers than a child without the familial form,” says Dr. Julie Ross director of pediatric cancer epidemiology and clinical research at the University of Minnesota. That can be particularly tricky since both chemotherapy and radiation can increase the risk of developing another type of cancer later.

Dr. Ross says children with inheritable cancers need to be followed more closely than children with cancers that don’t run in their families. In addition, relatives must decide whether or not to be tested to see if they are carriers of the disease.

When Dick and his wife Pat decided to have a family, doctors told them there was a 50/50 chance that the disease would be passed on to their children. “We knew that the diagnosis would be sooner and that the treatments were more refined than when I was a child,” says Dick. “We thought it was well worth the risk.”

Treatment options expand and become more accurate

Their son Rich was born in 1981 and they knew within two months that he had inherited the disease. Five years late, daughter Caitlyn also received a positive diagnosis. CAT Scan technology allowed doctors at the University of Minnesota to target the tumors with more accuracy than they could when Dick was a child. Treatment options had also expanded to include laser and cryogenics to burn and freeze the tumors. Still, both children ended up needing external beam radiation, which in turn caused cataracts.

While the Rambergs have certainly been impacted by cancer, they are not defined by it. Dick was the executive director of the Minnesota State Council on Disability before he embarked on a second career as a financial advisor. Rich is a director of sales and marketing for Sony Pictures Entertainment in Los Angeles. Caitlyn has returned to St. Catherine University to complete her degree in psychology.

Dick, Rich, and Caitlyn have also actively pursued their passions in life, including music. A professional jazz musician who has toured all over the world, Dick started playing the clarinet when he was ten years-old. Rich is an accomplished bassoonist and Caitlyn plays the saxophone.

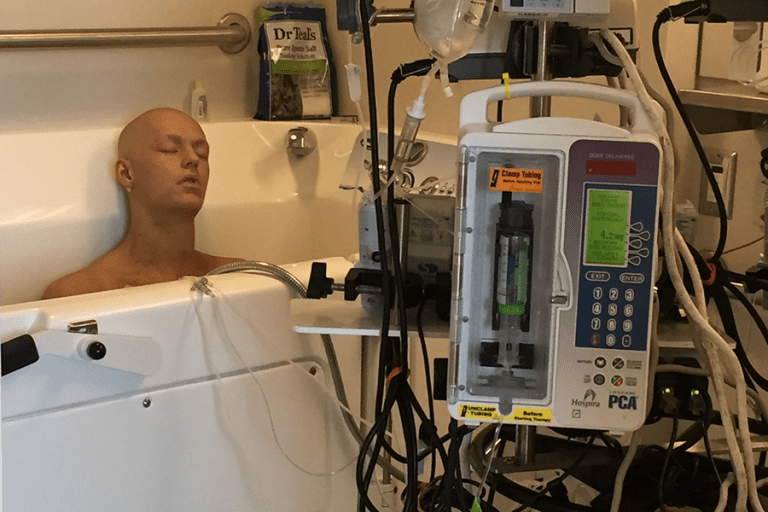

These days most of Caitlyn’s energy is devoted to raising her three-year-old daughter, Camille, whose own treatment for retinoblastoma shows how many advances have been made in fighting this cancer. “The doctors did an ultrasound a month before I was due and they saw a little speck in her eye,” Caitlyn remembers. Camille was induced three weeks early and the doctor immediately performed an eye exam. She started six months of chemotherapy, laser treatments and cryogenics when she was only five-days-old.

The most wrenching part of Camille’s treatment for her mother was making the decision to have Camille’s left eye removed when she was nine-months-old. “I was expecting the treatments but didn’t entertain the thought that she could have her eye taken out,” says Caitlyn. “But the doctor said it was between that and external beam radiation, which has complications like facial deformation because the bones don’t develop the same way.”

Hope for the future

While Camille is still too young to learn an instrument, she loves to dance to her grandfather’s music. She goes to checkups at the University of Minnesota every three months and her family is eagerly waiting for the day she turns five, which is when the odds of developing further tumors decrease dramatically.

In the meantime, the Rambergs are passionate advocates for early eye screenings for all children by qualified doctors and ophthalmologists. “Early detection—that’s the key to it all,” says Dick. And they wish for an even brighter future for children impacted by their disease. “I asked my doctor how close we are to being able to genetically fix this cancer before birth,” says Caitlyn. “He said not in my lifetime, but in Camille’s. So I’m really hopeful.”

* Update: We are sorry to announce that Mr. Ramberg passed away on March 7th. Read his obituary here.