When you think of childhood cancer treatments, turning a tumor into an ice ball and melting it is probably not the first therapy that comes to mind. But Alex Huang, MD, PhD at Case Western Reserve University thinks the method could boost immunotherapy effectiveness for kids with rhabdomyosarcoma.

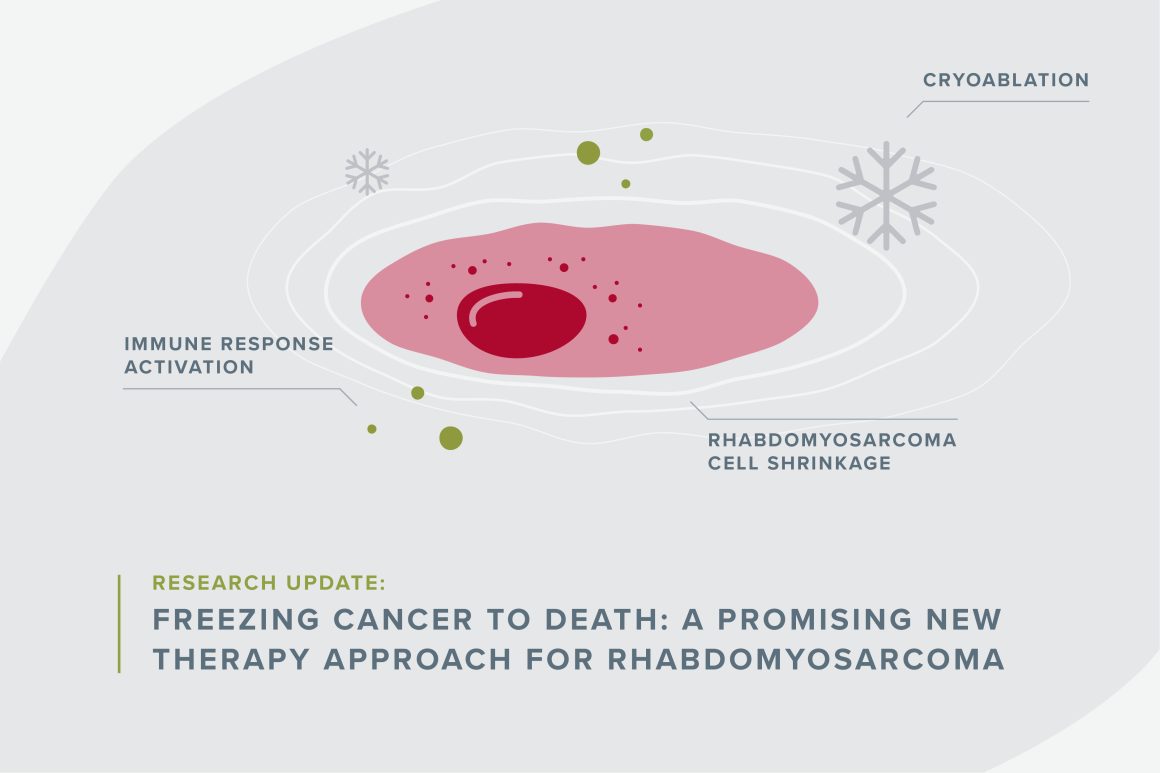

Freezing cancer with a gas like argon or nitrogen is already commonly used to help ease pain in patients with metastatic cancers. Called cryoablation, it involves inserting a wand-like needle through a patient’s skin and directly into the tumor. Doctors freeze the tumor and thaw it again repeatedly. “It provides pain relief by killing a nerve bundle. It can also shrink the tumor, but the tumor usually comes back,” Huang said.

One of Huang’s colleagues, an interventional radiologist, uses cryoablation to manage pain in adult cancer patients with bulky tumors, and occasionally, a strange phenomenon would happen. After his patients received the treatment for one of their tumors, some or all the tumors in their bodies shrunk or disappeared— even when these tumors had not been targeted by the treatment. This caused him to question whether cryoablation could treat tumors like rhabdomyosarcoma beyond pain relief, and he asked Huang to help him find out.

Using funding from Children’s Cancer Research Fund’s (CCRF) Hard to Treat Award, Huang conducted preliminary mouse studies to see what was happening in rhabdomyosarcoma on a cellular level with fascinating results.

His investigations revealed that after cryoablation treatment, the STING pathway (the part of the immune system that says, “please come help”) drove the rest of the immune system to fight cancer cells. This is remarkable because rhabdomyosarcoma typically prevents the STING pathway from doing its job, indicating that cryoablation is helping the immune system find and attack the cancer cells.

Typically, cancer can grow freely in part because it shuts off the STING pathway, which is essential to getting the immune system to help fight it. When the STING pathway is off, no alarm bells are alerting the immune system that there are foreign invaders, and the body does not fight or attack the cancer.

However, freezing and thawing tumor cells makes cancer cells expand, explode and spill their contents that flag them as cancer. The STING pathway recognizes the pieces of the cells as bad and rouses the immune system to attack the tumor cells anywhere it can find in the body, making tumors shrink or disappear for some patients.

“It has what’s called an abscopal effect,” Huang said, adding that cryoablation’s abscopal effect has already been shown to help adult cancer patients.

“Now we know there is an immunological aspect...how can we exploit it?,” he said. Huang thinks he can effectively get rhabdomyosarcoma to attack itself by developing a vaccine in combination with turning the STING pathway switch on in rhabdomyosarcoma tumors. Switching the STING pathway on in tumors will make them more susceptible to immunotherapies because the body will be able to recognize the cancer. Some patients do not have enough of the STING pathway component to make cryoablation effective, so he’s also developing a way to screen for it.

Thanks to support from CCRF donors, Huang has gathered enough preliminary data to apply for an R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health to further investigate cryoablation as a combination treatment option for kids facing rhabdomyosarcoma. If awarded the grant, he could include cryoablation as part of the treatment options for some patients.

Your donation funds scientists like Huang.

Your support propels bold ideas forward and empowers researchers to discover treatments that are better and safer for kids, and ensure every child can have a long, healthy life after cancer.