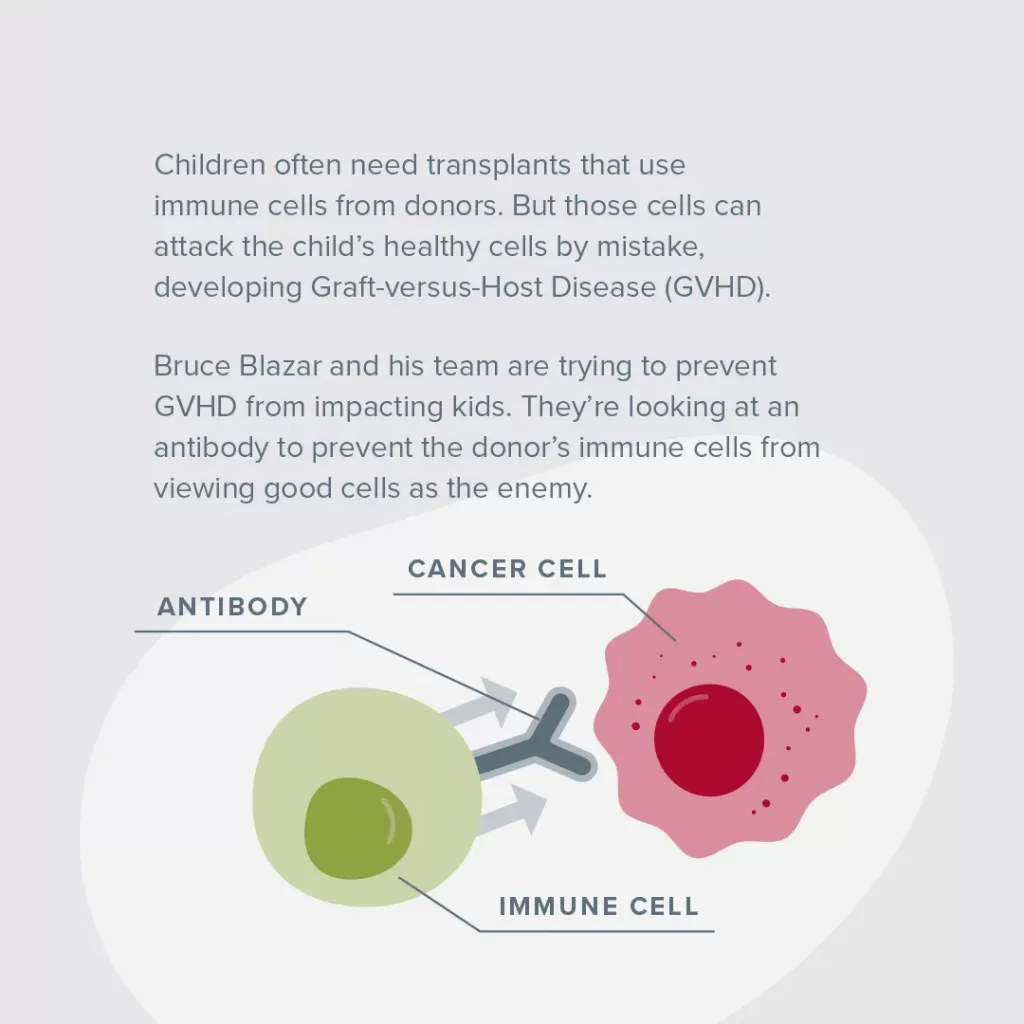

Kids like Alex often need blood or marrow transplants (BMTs) as part of their treatment plans. Typically, these transplants use immune cells (T-cells) from a donor, like a sibling or a match from a registry.

After a transplant, a few things could happen: the donor cells will attack primarily the child’s cancer cells (or “bad cells”) in her body and/or the donor’s cells will attack the child’s healthy (or “good”) cells.

Read Easing the Pain of Transplant - Alex's Story

When a donor’s cells attack a child’s good cells, the patient develops what’s called Graft-versus-Host Disease or GVHD, and it can be devastating to kids already facing tough diagnoses.

Overall, GVHD impacts 30 to 60 percent of transplant patients and is a major source of mortality. It comes in stages, and includes a vast array of infections, from breathing problems, debilitating digestive issues, painful rashes and more. Sometimes, the disease can cause irreversible damage to vital organs. The chronic form of GVHD, which shows up later on after transplant, is the most common reason for late mortality. Treating GVHD may mean even more drugs, like steroids, are pumped into a child’s body. Even if a child survives their cancer, the side effects can plague them for the rest of their life.

Previously, scientists believed that mild forms of GVHD were a good thing, showing that the transplant was doing its job. Recent studies have shown that GVHD is actually associated with lower cancer survival rates.

For some, being given a BMT and getting GVHD feels a lot like trading their old fatal disease for a new one.

Through the work of Bruce Blazar, MD, Regents' Professor of Pediatrics in the Division of Blood and Marrow Transplant & Cellular Therapy, Children’s Cancer Research Fund intends to erase GVHD altogether.

Learn more: A Crash Course in Childhood Cancer Terms

Blazar’s team has worked for decades finding innovative ways to prevent GVHD from impacting kids. Already, he and his colleagues have brought several GVHD-fighting treatments to clinical trial, including the only 2 drugs with FDA-approval to treat chronic GVHD.

Today, he’s studying a brand new idea, using the properties of a microscopic biological pathway in mouse models, which he hopes will eventually improve patient outcomes.

In order for the body to work properly, cells (proteins and more) send chemical cues to one another in a long chain of signals, called a pathway. These cells adjust their cues to help the body carry out a task, like healing a wound or attacking a disease.

In the case of a transplant, the new cells (T-cells) come into the body, take a scan of their new environment and kill what they view as the enemy. The hope is that they only kill foreign cancer cells, but in the case of GVHD, “the enemy” includes healthy normal cells, too. Currently, it’s difficult to limit what the donor cells attack, and there’s no way of knowing who will develop the disease.

Blazar aims to manipulate what is called the VISTA protein and its pathway. He will use an antibody to prevent the donor’s T-cells in a patient’s body from viewing good cells as the enemy.

The protein antibody will cause a series of adjustments in its pathway that will sort out the immune cells that set off GVHD, and keep the good donor immune cells which will only attack the patient’s cancer cells.

“We hope we’re able to have cells remaining that only have the positive aspects,” he said. We want to get rid of the cells that are causing harm, and the remaining cells can continue unimpeded.”

Today, this kind of antibody shows promise for solid tumors, and Blazar believes the data and theory could work well for leukemia, lymphoma and other types of childhood cancers.

“We’re hoping to bring it into blood and marrow, given as only a single dose. It has the possibility of getting rid of the side effects of transplant, specifically GVHD,” he said. “CCRF funding has allowed us to do high-risk, high-impact work and successfully compete for National Institutes of Health grants. CCRF funding has been absolutely critical for us. Such studies ensure we can continue to find new approaches to improve the lives of BMT patients.”

Kids Deserve Better, Safer Treatments

We believe kids fighting cancer deserve treatments that both eradicate their cancer and allow them to live full, healthy lives. With only 4% of federal cancer funding dedicated to childhood cancer, your support is crucial to finding safer, more effective therapies for kids battling cancer.