Alex Huang, MD, PhD, at Case Western Reserve University, said you’d call him crazy if he told you the exact same combination of drugs used to treat osteosarcoma 40 years ago is being used today.

“But that’s the truth,” he said. “And I’m just trying to make a difference.” Thanks to support from generous donors like you through the Zach Sobiech Osteosarcoma Fund, Huang could make a difference soon.

Pediatric hematology/oncology is near and dear to Huang’s heart for many reasons, but more than anything else, losing his 12-year-old cousin to osteosarcoma when Huang was 11 years old drives him to research difficult-to-treat, rare diseases.

He has searched unceasingly for readily available drug options that could cure osteosarcoma in its deadliest form, so kids won’t continue losing their lives to ineffective drugs -- the same ones that failed his cousin decades ago.

Recently, Huang found a pill called Vactosertib that he is extremely optimistic could become a widely used therapy.

Designed by the drug development company MedPacto in Seoul, South Korea, the therapy was originally made to treat colorectal and other cancers in adults. But Huang had a hunch it would work for difficult-to-treat, metastatic osteosarcoma.

“I approached the company, and I said you have a drug that I think might work in osteosarcoma. Would you mind sending your drugs to me to test in mice?” he said. They agreed to collaborate with Huang and the results were remarkable. On its own, Vactosertib reduced the number of osteosarcoma cancer cells, the size of a tumor and the amount of cancer spread in the mice.

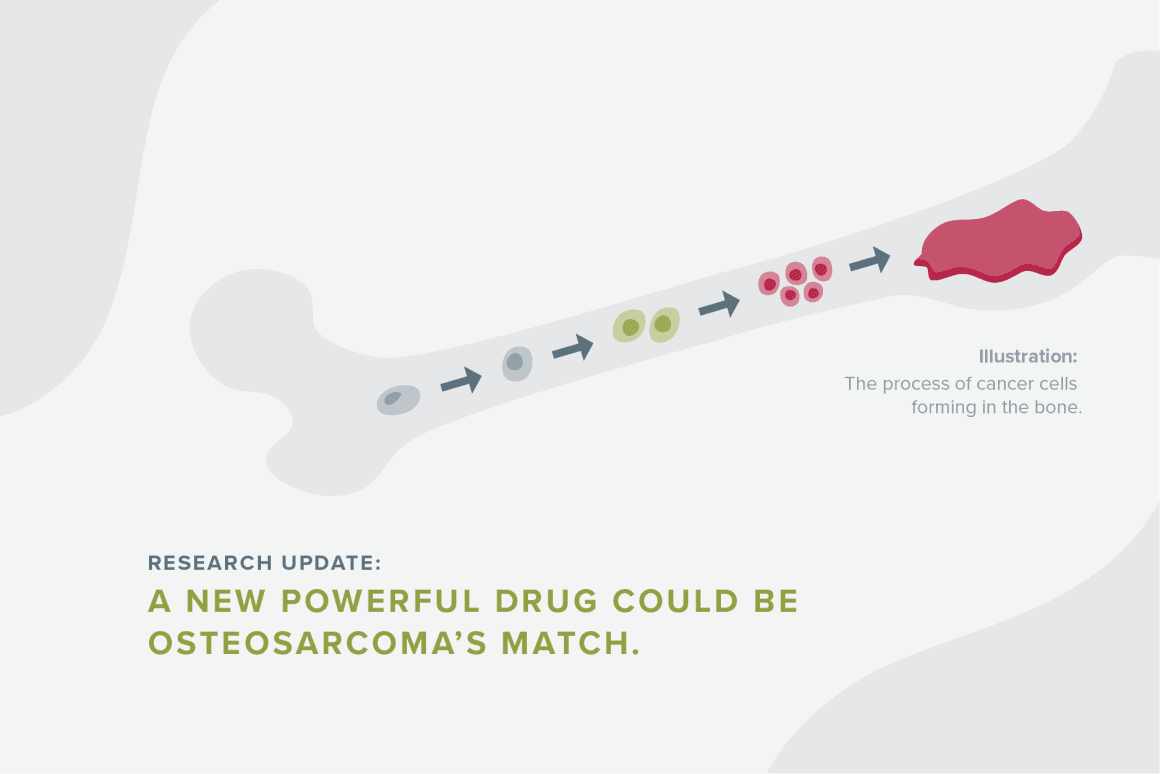

It works like this: A gene called TGF beta-1 is supposed to do good things, like prevent the body from creating too much inflammation. But in kids with osteosarcoma, TGF beta-1 supports tumor growth and prevents immune cells from attacking the cancer cells, allowing osteosarcoma cells to multiply freely and travel to other places in the body. As it travels, very few immune cells successfully attack the cancer. The drug aims to stop TGF beta-1 from suppressing the immune system and supporting tumor growth in patients.

The initial mouse study helped MedPacto secure Orphan Drug Designation (ODD) through the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). “Based on the data, the FDA agreed that this drug has promise to eventually cure a rare disease,’” said Huang.

Part of why osteosarcoma treatments haven’t changed in decades is because the disease only affects about 450 children and adolescents under the age of 20 each year in the United States. It’s typically not profitable for a pharmaceutical company to develop therapies for a disease that doesn’t affect many patients. The FDA created the ODD through the Orphan Drug Act to incentivize rare disease drug development, aiming to make it profitable for companies and ensuring that kids facing orphan diseases get new treatments.

MedPacto was so blown away by Huang’s study results that the company changed its strategic plan for the drug to focus on osteosarcoma. In addition to the pill’s effectiveness in preliminary studies, he notes that the drug hasn’t revealed any side effects. Compared to current treatments, which increase infection risk, cause painful mouth sores, hair loss and more, this is extremely promising news.

Now, Huang’s team is focused on finding the best way to combine Vactosertib with other therapies, making it even more effective for kids facing the deadliest forms of osteosarcoma.

In August 2022, Huang obtained permission from the FDA to proceed with a Phase I trial for patients ages 14 and older. Currently five sites across the country will be participating in the trial and more may be joining soon. Anecdotally, the drug is already working successfully in patients who have received it through the FDA’s Compassionate Use Authorization.

One 12-year-old with recurrent osteosarcoma and a history of brain and lung metastasis took Vactosertib for eight months. The child remained free of metastatic disease except for a small disease recurrence in the hip that was treated with additional local therapy.

“Being orally available, Vactosertib has low toxicity and can preserve a good quality of life.” said Huang. “[Sarcomas] are really tough nuts to crack, but I think we are well positioned to make an impact in the immediate future.”

Your donation funds scientists like Huang.

Your support propels bold ideas forward and empowers researchers to discover treatments that are better and safer for kids, and ensure every child can have a long, healthy life after cancer.