We had it good. We had a brain tumor survivor who was thriving. Sure, he had late effects: Stroke damage, hearing loss, partial blindness, speech difficulty, cognitive delays (which is a nice way of saying his brain and his mouth don’t work well together), drop foot causing trouble with balance, issues controlling body temp, fatigue from processing input and a seizure disorder that was controlled by medicine.

But we still had it good. We were thankful for the gift of his time with us, and we worked hard to help him when we could. We enrolled him in hours upon hours of speech, physical and occupational therapy each week. At home, there were even more hours of reading, writing, practicing skills to help him keep up with his peers. We were at peace. Our son was happy.

Then he turned 9. The day after his ninth birthday he had a seizure. He was standing in the middle of the living room, frozen. His arms and hands were locked out. He couldn’t speak.

All I could hear was his struggle to breathe, as he tried to stay upright.

I ran to him, carried him to the couch and held him as he continued to seize. I whispered in his ear, “You’re okay buddy. Mommy is here, and I’ve got you.” My heart was racing; I was feeling the panic sink in. No, no this is not happening to my baby.

The seizure lasted about one minute. I continued to hold him, caress his precious head and explain to him what had just happened. He was tired and told me that he was scared because he couldn’t move his legs to go where he wanted, and words in his head were stuck there.

After a while, he wanted to get back to being a 9-year-old boy. Ok, good, I thought. I continued to creep on him all day. Spying, lurking, searching for the peaceful feeling I had had the day before.

A few days later it happened again. And again, and yet again; each seizure lasting longer and getting stronger. The days rolled into weeks. Soon, he had intense nightly headaches, nausea on and off, and the fear settled in deep.

His teachers were notified; seizure rescue plans were reviewed and updated.

Typing out what your child’s seizures look like in detail, writing out how to help him, and what to say when I wasn’t there: It made me sick to my stomach.

With each action I took to keep him safe, the peace I searched for slipped farther away.

The fear that brain cancer had come back sucked the breath from my chest and gnawed at the walls of my stomach. I prayed this would not be the next chapter in his life, that cancer would not come back and rob us again. He had (we all had) been through enough.

Witnessing Trauma, Over and Over

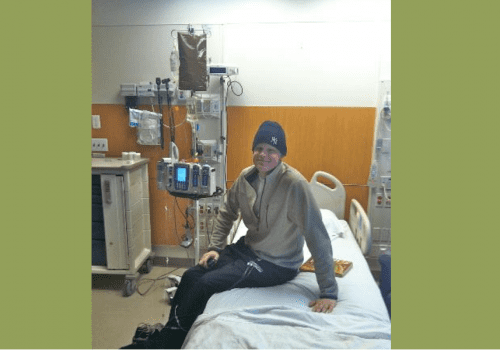

Connor completed an MRI which ruled out the possibility of brain cancer. His labs revealed no concern for leukemia (which is a secondary cancer risk until he is 10), and we were referred to a neurology team. We took in a small sigh of relief. We were happy the tests did not show any tumors growing in his head, but the MRI also showed us, once again, the massive damage his brain tumor had left behind.

We were still dealing with the unknown. And at times, the unknown is a heavier burden.

Connor kept having seizures.

EEG tests were given, meds were increased, new meds were added, but they kept happening: At school, at home, during dinner, at birthday parties, during our morning snuggle, in the evening, while sleeping, while playing. Any second of any day a seizure would strike.

It rips my heart out, hearing him struggle to get his words out. It comes with an unbearable weight. His cries for help, begging me to make them stop, haunts me in my dreams. It’s witnessing trauma, over and over and over again.

Flying with Broken Wings

Now, nine months later, we are still trying to find the magic combination to make Connor’s seizures stop. I don’t even like writing the phrase “Connor’s seizures.”

He doesn’t own them, he didn’t want them and he didn’t ask for them— they don’t belong here.

He wants to be able to ride his bike without having a seizure; he wants to be able to go swimming without a life jacket because, “Mom, I already know how to swim.” He wants to have sleepovers at friends’ houses. He wants to be the kid who isn’t tormented.

We will continue to search for the answers. But here’s the thing: we don’t know if they ever truly will. We are in another chapter of Connor’s life. A life that is still full of smiles, hugs, play dates, camp fires, school, favorite treats and so many wonderful things. But there is an awful sting that comes with every seizure, every cry and every sleepless night.

For the first time, I feel like I cannot help him.

The other night, I asked Connor what he thought about all of this seizure business going on. “Well, it’s kinda confusing. Having seizures makes me sad, but you and daddy always get real close to me when I have one and that makes me feel happy.”

He is my greatest teacher reminding me that being his mom is what he needs most from me. I am raising a boy who is flying with broken wings, and he is doing it beautifully.

Written by Mindy Dykes

Mother of 9-year-old Connor, a brain tumor survivor

My son was diagnosed at 6 weeks old with a brain tumor. It was massive and required emergency brain surgery and an aggressive plan to treat the remaining cancer cells. Connor made it through surgery, survived chemotherapy and a bone marrow transplant all before he was 7 months old. We, as well as friends and family, were in shock and disbelief. Our family could be lifted up or devastated by questions asked or comments made. We learned quickly why it is so important to consider every word uttered in a time of crisis.